composition should be as free as home cooking

an Artist Manifesto – 12.15.24

Having little contact with the pre-1998 world, my generation of artists appears to be stranded alone on an island in time. This is in utter contrast to the way the history of classical music seemed to be presented to me as a student, as eluded to in Timothy S. Murphy and Daniel W. Smith’s article, What I hear is thinking too: Deleuze and Guattari go Pop (2019). They posit, “If pop is a rhizome, then it may be helpful to think of the Germanic tradition of formal composition from Bach to Schoenberg… as an example of the linear tree system.”

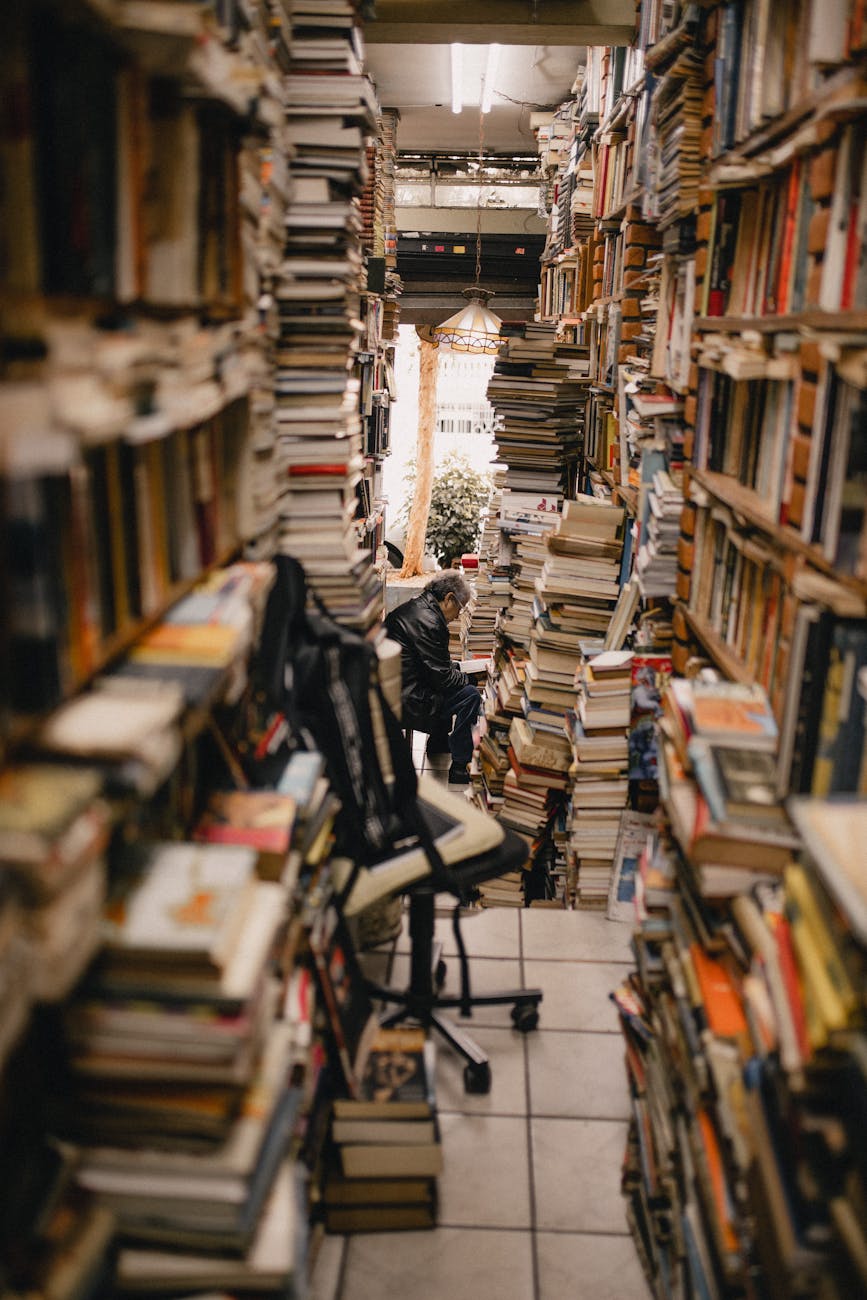

Through technology — and the fact that I can have a survey of all of western music history spread between twenty YouTube tabs open on Google — the toolset I use and knowledge I’ve gained has been presented to me in the form of a rhizome, not a tree system. I don’t ever need to leave my apartment in Washington Heights to touch the very boundaries of the known universe, to dig into the most fringe topics at any point in history at any pace I like. In a sense, all of the past that we know of is happening now. Further, all of the past is happening within us, constituting the stage of our observable inner worlds. The current forefront of musical style is characterized by a response to rich, interconnected multiplicities and flows. I tend to observe two camps: one that embraces and one that retreats from, putting into motion two divergent spirals in the outpouring of genre and topic fusion we so often see in Contemporary Music.

I wonder if we can hold fast to both an old-school transcendent scope for our works and this new world of multiplicities and constant evolution. Understanding in greater depth what inspiration does for us is only part of the picture. I am convinced that the treasure of classical music lies in the fact that a piece is a banner that unites the composer, the performers, and the audience, and that this dynamic trio plays a small role in uniting the world (anyone can be an artist, performer, or member of an audience).

I reject the contemptuous aspects of that Germanic lineage which imply that the composer-as-hero archetype — conquering music alone — is central to our art.

Mahler is a hero to me, but Mahler would never rise to a household name without the orchestra, without performers. Performers would also be out of a job without an audience and without music to perform. The fly and the spider are co-creators of their dance, and an audience engages in a co-creative activity with the composer, building the piece in their minds. The distinctions between independent machines begin to dissolve when all three elements are unified in a performance. Because of the new richness and depth of this unification, a piece takes on internal agency with dreams and aspirations, becoming what I like to refer to as “ringing art”.

/

From time to time, I become entranced with superficial, self-oriented progression. The current zeitgeist in terms of musical choice-making seems pressured, hurried, lonely, and hungry — this starvation being brought about by a retreat to a comfortable, yet isolating space alone.

In moments of fleeting clarity, I want to grab every living composer by the shirt collar and rattle them awake, reminding them that our practice is something akin to a miracle. If we take composition for granted, if we feel that bit of music in our guts and ignore it, we take life itself for granted.

Invoking George Rochberg, I often wonder if there may come a day when I regret not investing more energy, more thinking, more heart into my music. Will a day come when I forget the importance of my playing a small role in a much larger musical ecosystem? I ponder the ways in which I can speak honestly through music, and of the bewilderment that comes from recognizing that the desire for honesty directly interferes with real, true authenticity of an unbridled flow of art. The moment one does something in a seemingly authentic way, one inadvertently moves the goalposts regarding what constitutes authenticity, as there’s always something deeper, more authentic, more true to oneself.

Authenticity becomes futile as the eye can never turn inward to see itself, always requiring a mirror, and that mirror is oftentimes someone else’s art. All I know is that I am no hero, I am nothing without the economy made manifest by the dynamic trio of composer, performer, and audience, and I can’t do it all alone. Nobody can and nobody has.

/

By way of introduction,I am a violinist in trade, a guitarist in heart, a pianist in spirit, and a proud collector of obscure instruments. I did the bulk of my pre to mid adolescence in an old Western Maryland coal mining town just south of the West Virginia border, beginning my musical journey in school orchestra under a native trumpet player who had recently start taking string lessons from his wife, who had a private violin studio. In a town with limited musical resources, my parents later founded a 501(c)(3) youth orchestra, and I landed in violin lessons over Skype for six years when the best teacher available to me relocated to Michigan. Eventually, I found myself working with a Baroque Specialist in Tallahassee, Florida throughout high school, and spent time teaching myself the rest of the instruments I have in my quiver today, particularly jazz and classical guitar.

This is when my musical life picked up speed. Originally on a pre-law track, my innate pull toward music brought me to a last minute audition at Florida State University where I was — to my surprise and delight — accepted into their Music Education program. Being around more experienced musicians, I was inspired to find a home in the FSU computer lab composing on Finale software at every free opportunity.

I took on a very intense regimen of writing at an extremely prolific rate — often staying into the wee hours of the morning since I had become friends with the computer lab staff. This was the bud of my composing obsession. Two Music Theory graduate students took note of my technical facility in model compositions during Theory III and IV, and took me under their wing. They recommended I take an Intro to Composition course and set me on my journey toward joining the composition studio of Dr. Stephen Montague, stepping in for the late Dr. Ladislav Kubíck.

Dr. Montague enjoyed speaking in riddles, and gave me a profound piece of advice or irritating little koan that I latched onto, which became central to my early development. He said, “Never write a piece that is too long.”

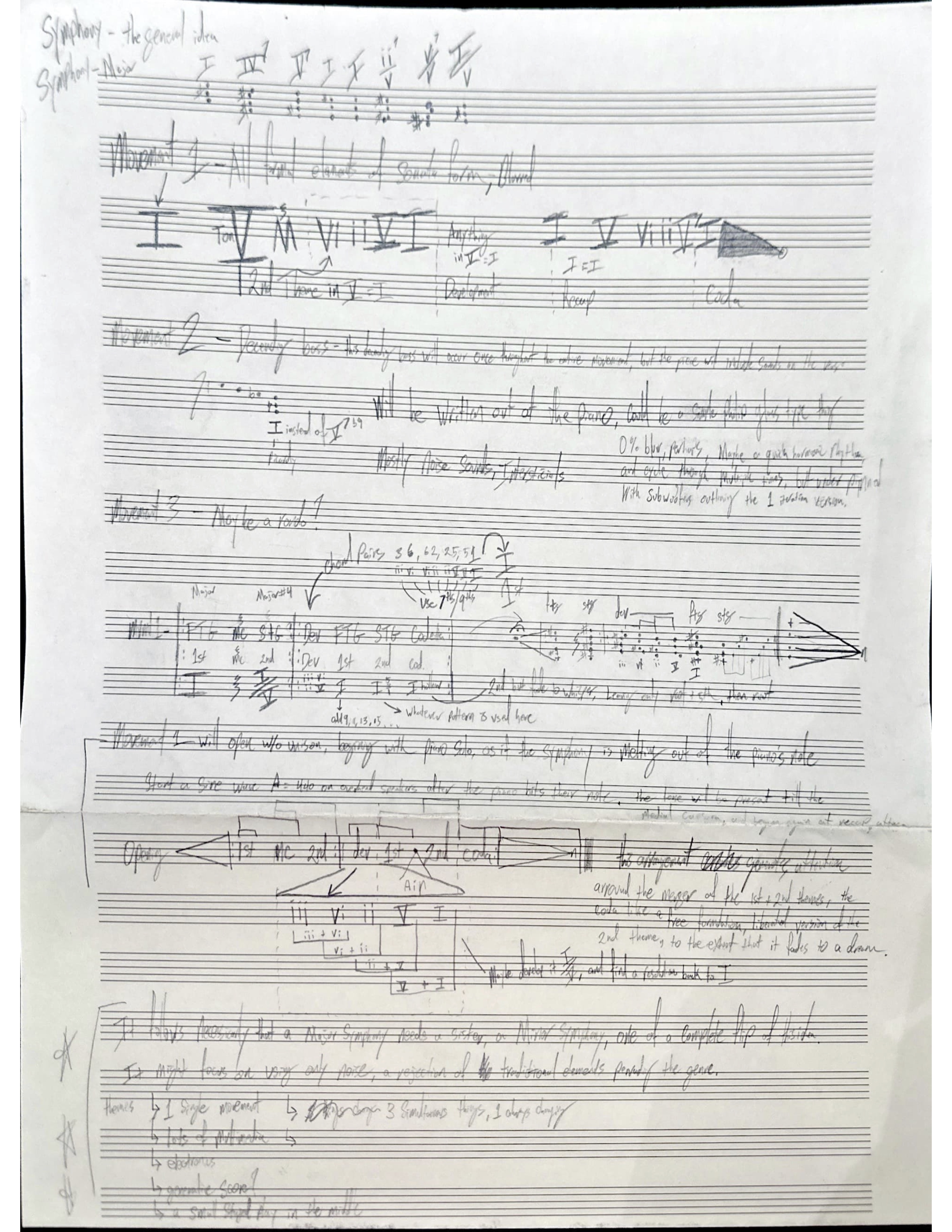

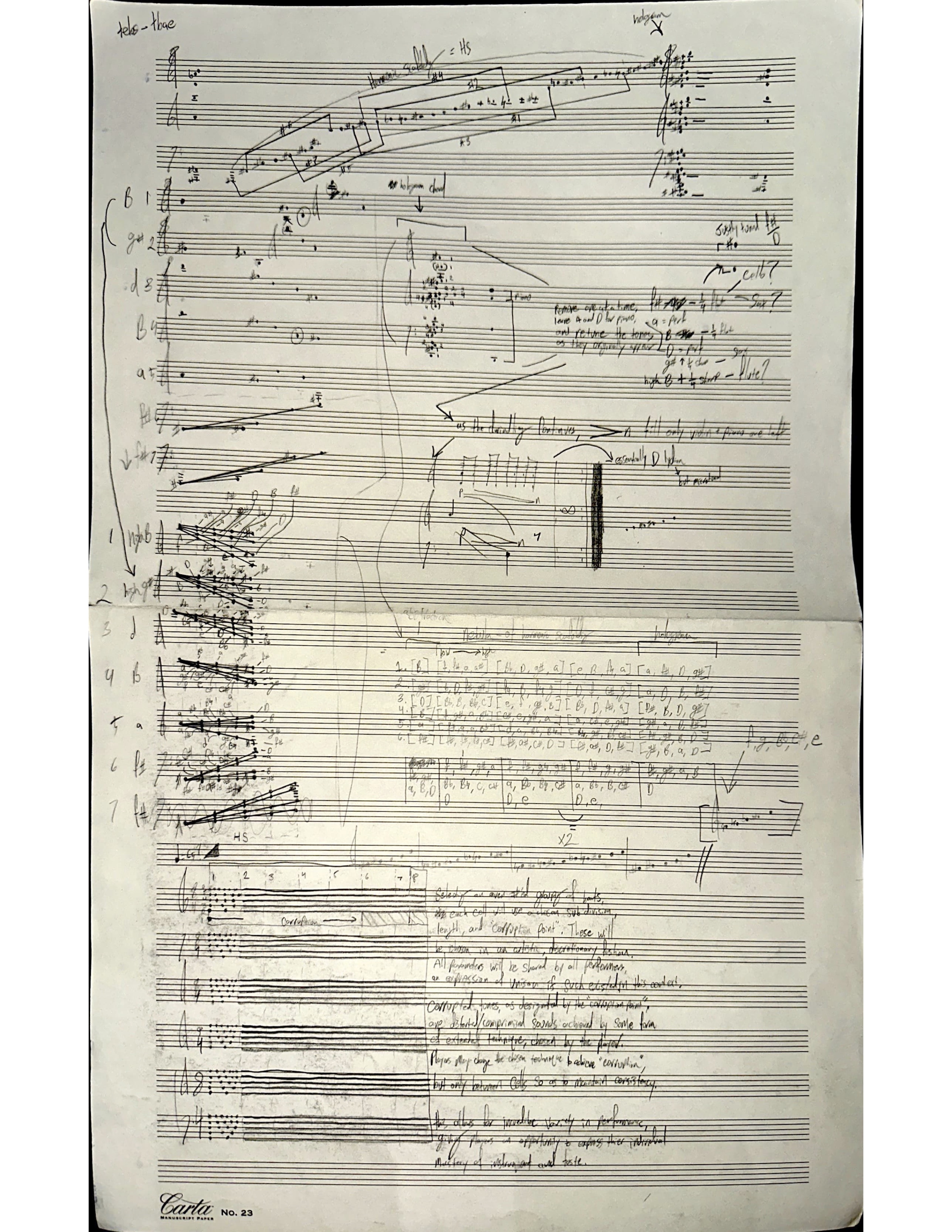

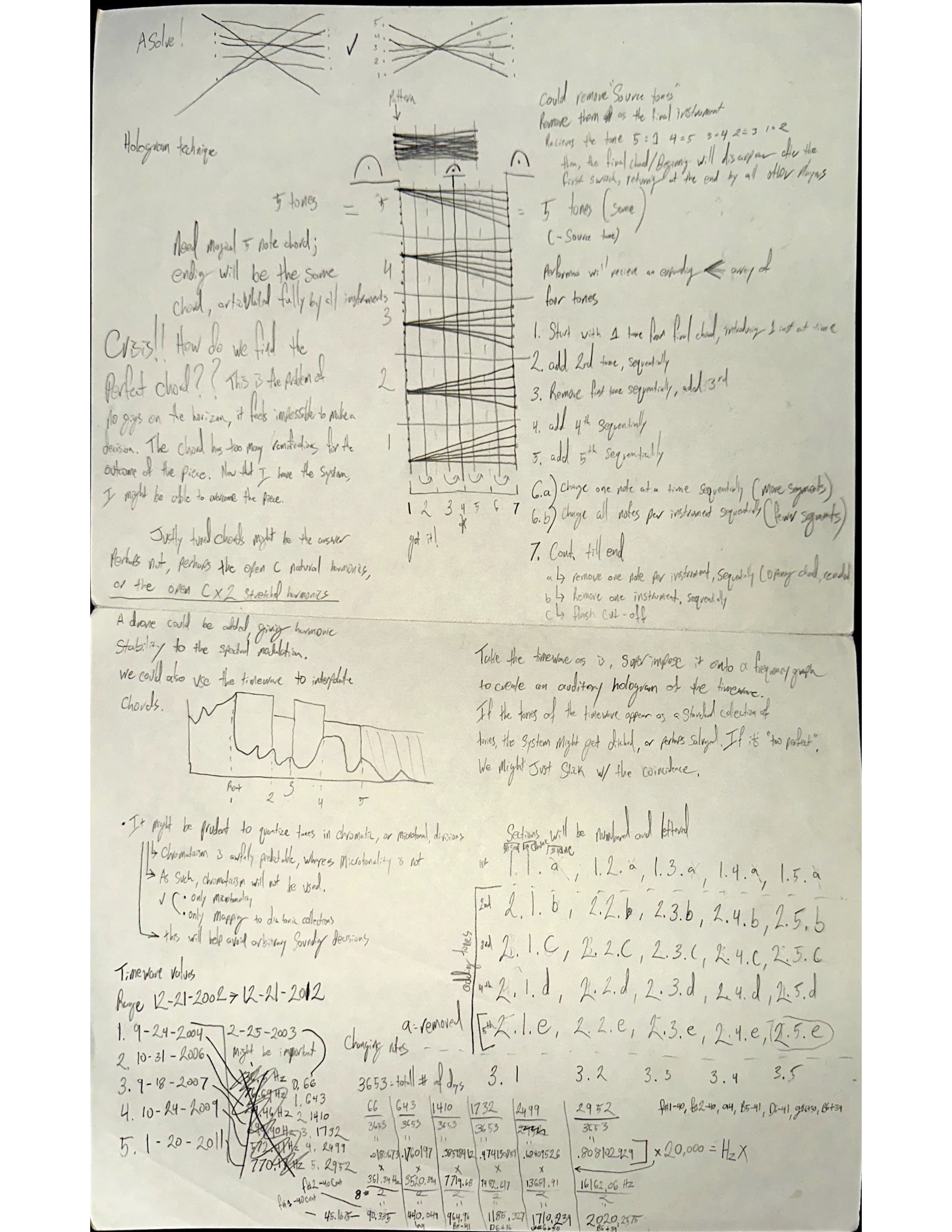

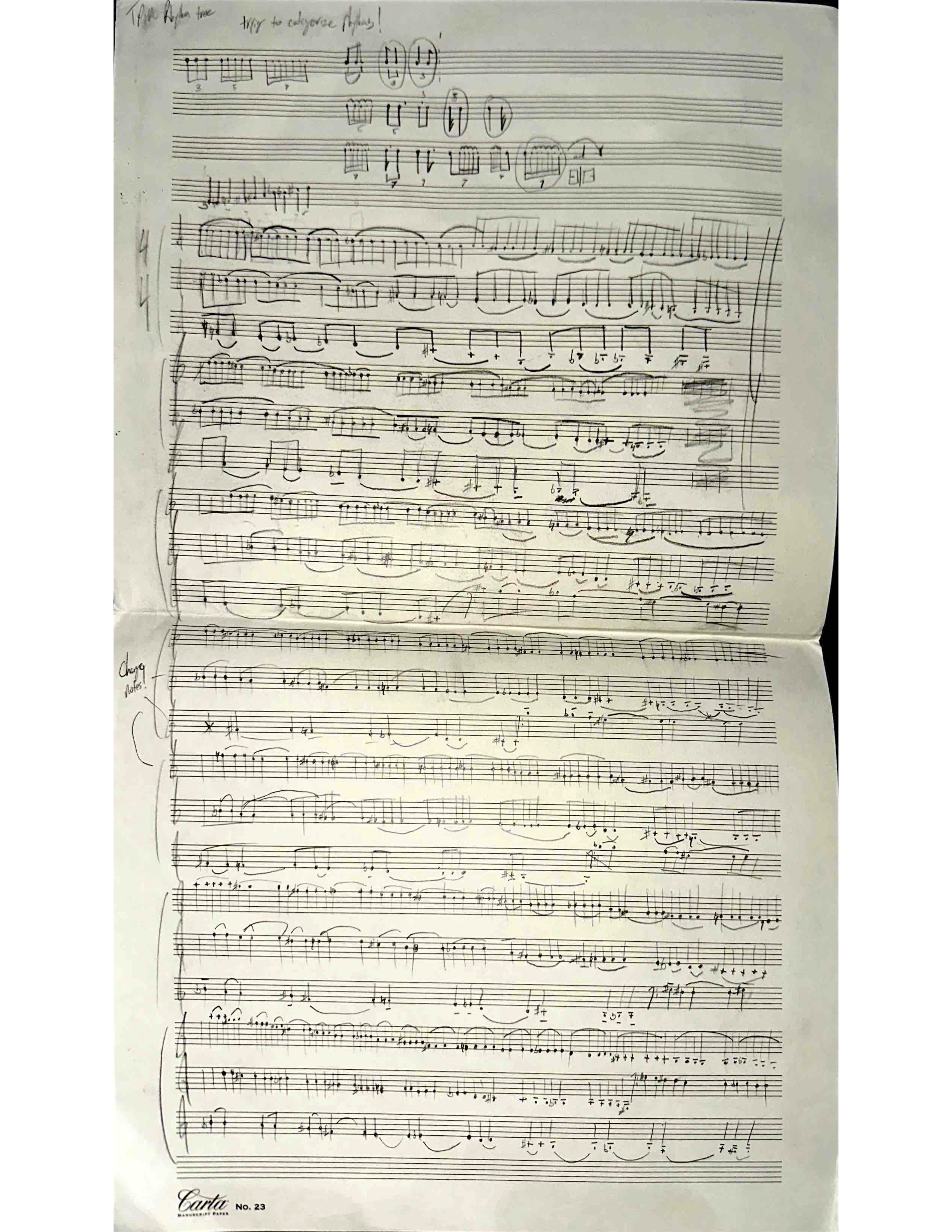

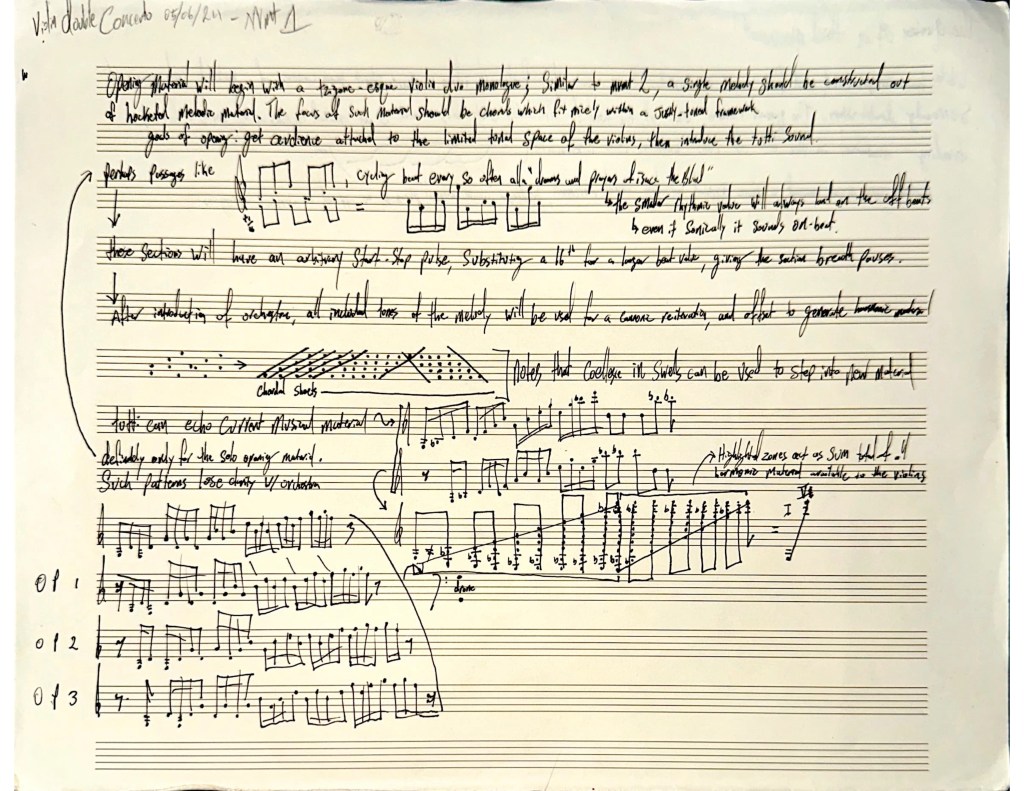

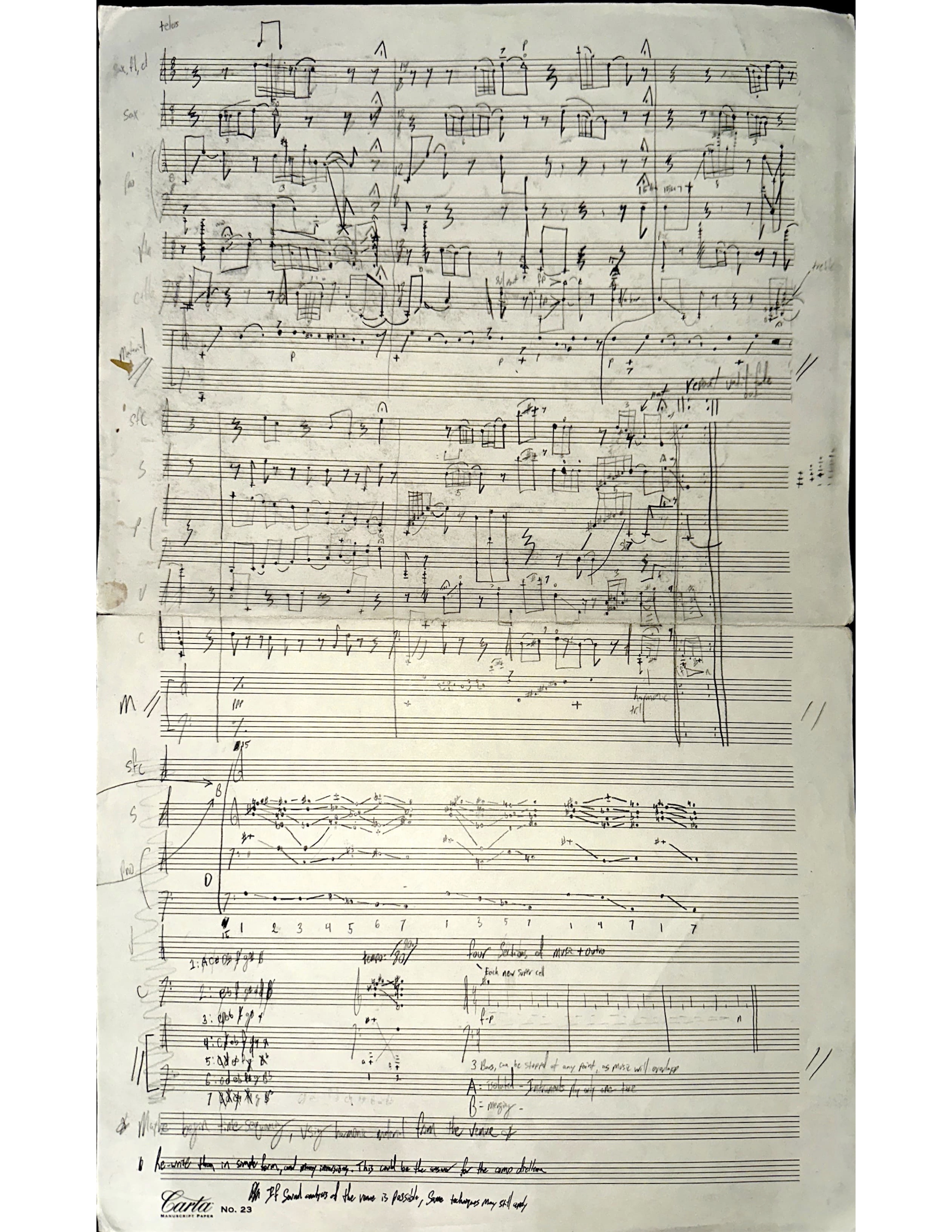

I soon threw everything I had at composition, knowing if I didn’t take this opportunity it’d slip right through my fingers: I wrote string quartets with drum-set and electronics, violin and timpani duos, Kreisler pastiche, Reich pastiche, Simon Steen-Andersen and Eric Wubbles pastiche, Chick Corea tunes in retrograde inversion, built out idiosyncratic 12-tone techniques on the back of unused receipt paper from the register at my 10-2am shifts at Tropical Smoothie Cafe, jazz and bebop tunes, performance art pieces, pieces for amplified lunchbox, pieces for Harley Davidson bikes, spectral composition, spoken word pieces, site-specific works for air-raid sirens (titled 100 Seconds to Midnight), and a remarkable quantity of bad pieces.

I developed an odd predilection about composition, too, where I tend to not care about whether a piece ends up being performed so much as whether I grew from the experience while writing it, or whether did it justice. In my defense, I had far more pieces to write than opportunities to write for at that stage. Even without many opportunities to write for, challenging myself to push the envelope as if I were an already well established field composer had a tremendous impact on my early development. I can admit this does still end up hindering me professionally as I haven’t put enough pieces up for competitions, choosing instead to proceed with the next piece right away.

/

Whatever Dr. Montague meant by a piece that is too long was still elusive to me, but I was determined to find out; the paradoxical solution to this riddle would eventually move me away from construction and symmetries an indicator of a piece’s completeness.

Dr. Montague’s mantra elucidates the true nature of composition in a very clever way. My analytical, constructive mind sees no definite method by which one can determine whether a piece is too long. In musical analysis, we generally take composers at their word concerning where an ending belongs, a double bar line.

Not everyone has foresight, as in Toscanini’s famously loose interpretation of Debussy’s La Mer. There is a clear way, nonetheless, through intuition. The ending of a piece “rings” and since I haven’t yet earned a PhD, I have no better word for it. When a piece rings, it has reached some sort of artistic brick wall where the piece takes on this certain magic quality, as if balancing a mountain on the tip of a needle. A piece that rings has mass, it has a gravity. It has a force that pulls material into the place where it belongs or it outright rejects new additions from its balanced system. Like a bad organ transplant, the piece is sickened by poor musical choice-making.

When I feel an ending coming up, I say to myself, “don’t touch it, it’s perfect just the way it is.” Ringing art is a plateau where a work or performance transcends the quality of the technique which birthed it, where positive reception is now primarily beholden to things as ephemeral and fleeting as chance, chaos, or fate. This is not to say the object is entirely beyond us at that point. One, as a rational, thinking thing, has as much control over that dimension as the capacity to cerebrally the heartbeat, breath, salivation, balance, sense of direction, or sense of fatigue.

One controls heart rate by managing the breath, controls salivation with mental imagery, and dilates the eyes at will simply from thinking about the brightness of the room. The way I see myself, my being, is not dissimilar to the composer-performer-audience trio. I live a rich, conscious life unburdened by the goings on of what the tempo of my heart is or how my eyes are focusing. A performance enjoys the same kind of freedom, being unburdened by the gritty detail of what section musicians are playing or the ongoing analytical chatter in the minds of the audience. When a performance is liberated to this extent the performance rings, and when a performance rings it is no longer bound by the sum value of its parts, taking on a magic, living quality.

/

I divorce myself from the notion that a piece of music is like a machine which aims to produce or evoke a reaction. In itself, it is a composer’s reaction, and has not yet unified the necessary components such that it becomes ringing art.

Speaking to twelve-tone music, my stance is that it is inappropriate — even disrespectful — to relegate tones to the role of musical fluff, i.e. gestural content for the sole means of getting from point A to point B. Instead I admire works such as Stockhausen’s opera project, Licht, where every layer — from the cosmic level of Michael, Eva, and Lucifer’s musical kernels to the minutiae of moment-by-moment orchestration — is in constant communication.

Approaching music from the composer-as-hero perspective unleashes a stallion of a question that cannot be fully overcome alone: how can I develop material for musical fodder in a way that is respectful, where the choice of tones is meaningful, where the material lives in cooperation with earlier and later points in the piece of music such that a single change in the musical-fluff has a cascading effect on all other parameters in the piece? This is awfully tricky. Future decisions affect past decisions, and those resolutions affect other decisions.

To me, it starts by asking a budding piece of music how long it would like to be, and I can only speak to a piece of music like this in a flow state. I believe that the old-school ideology of “inspired artistic activity” is actually quite within reach to most individuals. It seems to me the most inclusive aspect of our art, and simply a matter of attunement that is necessary to act on such inclinations. I find my way back to inspired artistic activity through the inescapable challenges of projecting my internal world outward, since every parameter can converse and interact with every other parameter in a composition like a network. Form communicates with tempi, harmony, choice of musical gestures, orchestration, so on and so forth to the extent that any change in one area has a ripple effect that forces me to renegotiate all other parameters at once.

/

Inspiration and flow serve to lift an artist out of this mess of integrated parameters, and a piece takes on internal agency and a voice when it finally moves from a cold network of machines to an object of the imagination with no clear distinctions between those myriad constituent parts.

My response to the current state of classical music can be summarized in a series of observations and deductions.

First, ringing art is the economy made manifest by the movement and flow of the composer-performer-audience relationship.

Second, the link between ringing art and the composer-performer-audience relationship appears to me similar to the link between one’s being and the constituent machine-like aspects of one’s unconscious mind.

Third, communication with a piece of music can be established when a composer enters a flow state, which is to say submerges oneself in a manner similar to what happens when watching an engaging piece of media, or engaging in sport.

It is no surprise to me, then, that inspiration can take center stage once more in music history; in theory, inspiration is like a location where a person experiencing flow can meet ringing art on equal footing. Like how inspiration lifts the 21st-century artist out of the mess of integrated parameters, so too inspiration allows the artist to make sense of the near limitless quantity of information moments away on cellular devices and laptops.

I can move forward because this new view of inspiration gives me leverage over both cognizing limitless information and using it in a practical context to create ringing art; it is not actually a dialectic, two true things in combat, but two inseparable sides to the very same coin. Reconfiguring inspiration helps me see there was never any opposition between the way musical information was conveyed to me and what to do with all of it, recasting the composer-as-hero across history as a collaborative venture.